The digital world is built by people. The decisions made by tech companies shape the way young people experience the digital world, and this includes the decision about how they design their products and features. This report documents a range of harms that young people experience as a result of decisions made by tech companies.

Extended use and addictive design features

Young people can be especially vulnerable to extended use designs or ‘addictive’ design features that attempt to keep young people ‘hooked’ on a digital product. These include push notification designed to pull young people back into an app,1 endless scroll, content recommender algorithms that are “optimized for addiction”2 (i.e., “trained” to maximize the amount of time young people spend watching videos)3 to removing video time markers4 or other features that might remind young people to log off and take a break.5 Currently, 36 percent of American teenagers aged 13-17 say they spend too much time on social media, and 54 percent say it would be hard or very hard to give up social media.6

In rare cases, this extends to a medical addiction, called Internet gaming disorder.7 An estimated 8 percent of American children who use the internet and games show signs of clinical addiction.8 More commonly, extended use design causes constant relationship harm. Intrafamily conflict around screen time is rife,9 and many teachers report conflict in the classroom over the use of digital devices.10 These can also cause physical harm, because they can lead to a loss of sleep.11

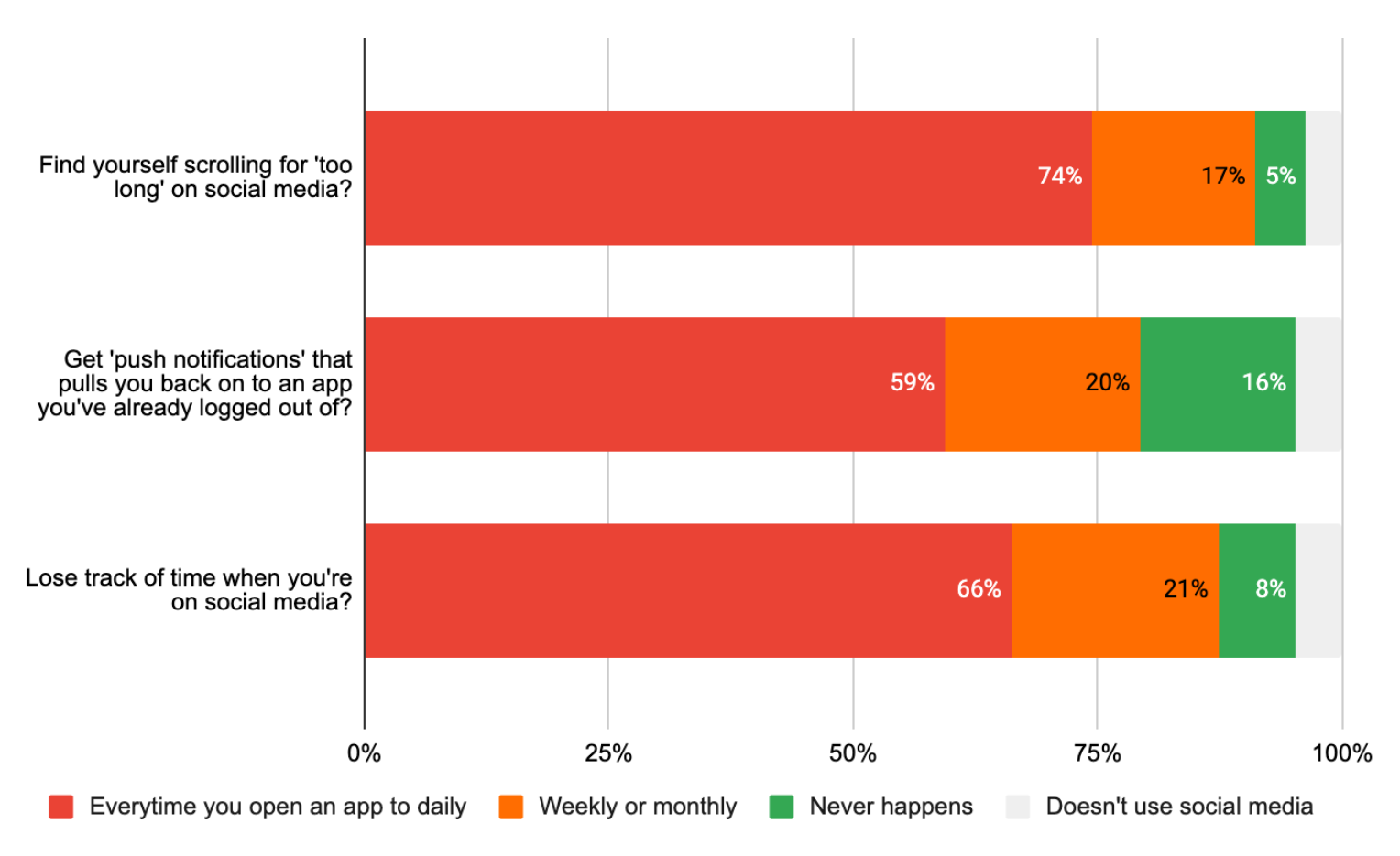

In March 2023, working with YouGov we asked 912 American teenagers if they had ever felt the effects of these extended-use designs and the results were telling. Three quarters of young people found themselves scrolling on social media for too long every day; features such as endless scroll and recommender algorithms trained to maximize attention work. The majority of American teens find themselves scrolling for too long. When they do log off, more than half get push notifications that ‘pull them back’ into the apps every single day. These are design features of apps that can make it even harder to log off, testing their will power. Again, the majority of American teens experience this every single day. Two thirds of young people feel that they lose track of time when they are on social media. The design decisions implemented to make social media platforms sticky and feel timeless clearly are working.

Not all American young people experience these design harms the same way, and our research found that Black and Hispanic teenagers experienced more of these harms than their peers.12 This is also confirmed by other research.13

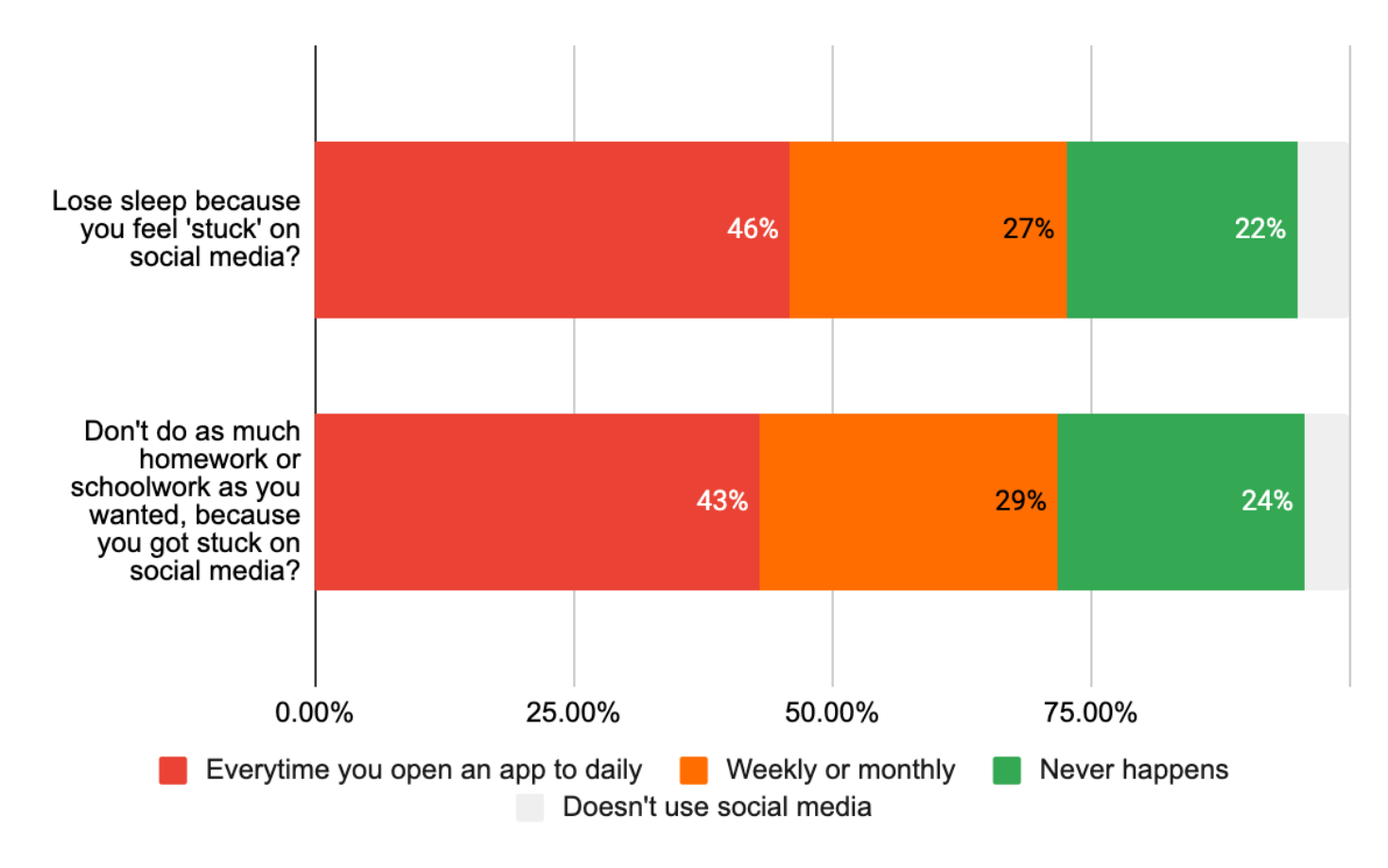

The consequences of this are demonstrable. Almost half of American teenagers report losing sleep because they feel ‘stuck’ on social media, and more than one third say they do not get as much homework done as they want to because they get stuck on social media.

‘Friend’ recommender features

Young people’s privacy is important and it helps to keep them safe. The design of social media features can make young people more private and safe, or less private and safe. As Meta’s own internal research highlighted, 75% of all ‘inappropriate adult-minor contact’ (i.e. ‘grooming’) on Facebook was a result of their ‘People You May Know’ friends recommendation feature.14 Likewise, features can help keep young people safe and private; where a young person’s account is defaulted to private, they are not immediately recommended as ‘friends’ or as accounts to ‘follow’ to adult strangers.

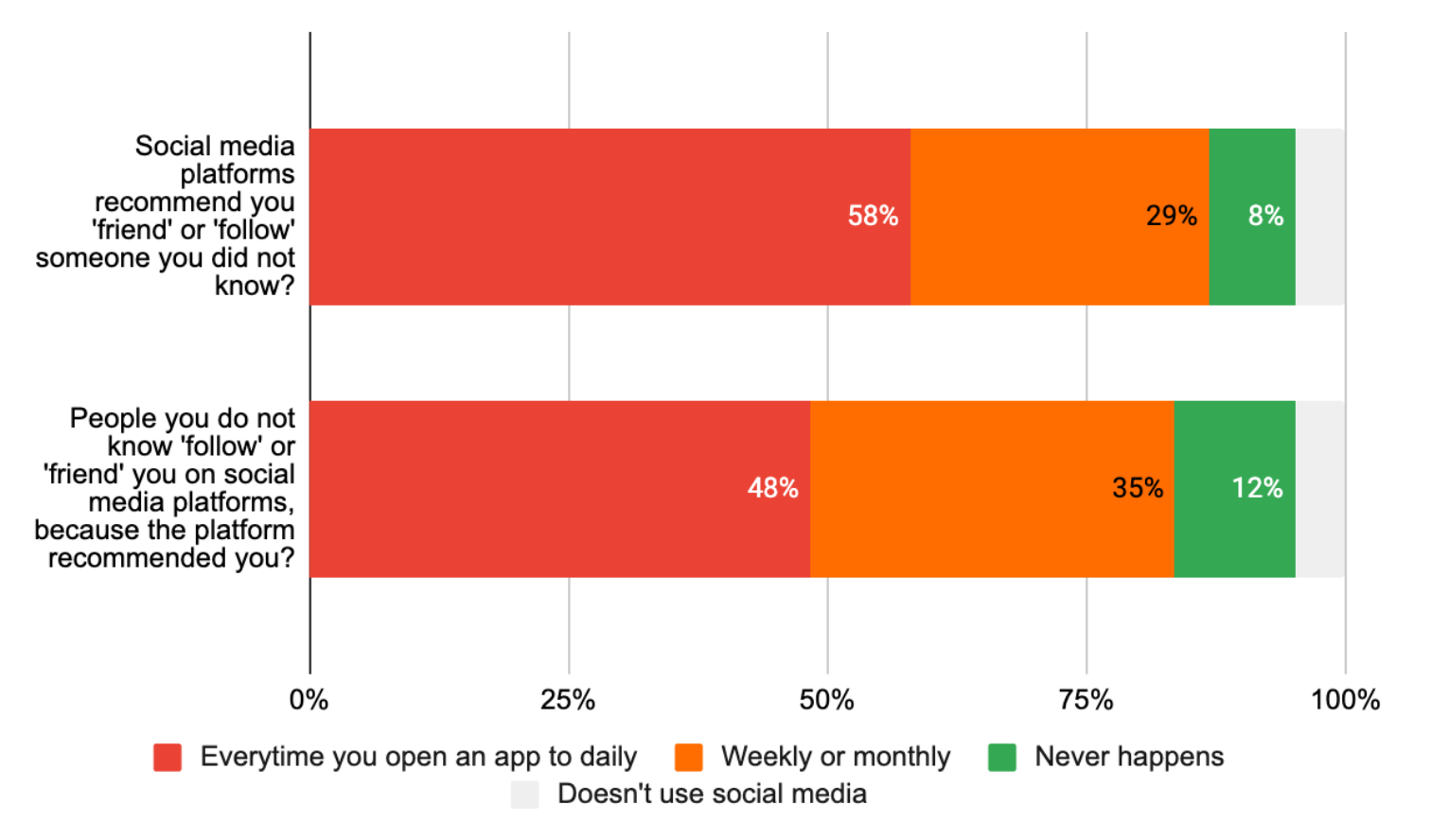

In March 2023, working with YouGov we asked 912 American teenagers if either a platform’s ‘friend’ recommender feature had recommended that they follow someone they don’t know, or that someone they don’t know has followed them because of this feature. This was extremely common, only 8% of young people had not been recommended to follow a stranger, and 12% had not been recommended to be followed by a stranger. While some of these may be celebrities or friends of friends, this creates real risks of contact with adult strangers that appear to affect the vast majority of American teenagers.

Not all American young people experience these design harms the same way, and our research found that teenagers who identified as LGBTIQ+ were more likely to be recommended strangers to ‘friend’ or ‘follow’ than young people who did not identify as LGBTIQ+.15

Excessive data surveillance

Young people are tracked, traced and surveilled online by most of the digital platforms they use. Companies harvest this data about young people to make vast profiles about them, in order to sell targeted advertising directed to children. However, children have a right to privacy and this data collection can create other risks, such as risks of data breaches (sometimes leading to identity theft) and security risks. These are not insignificant risks.

In 2021, 1 in 45 American children had personal information that was exposed in a data breach and 1 in 50 were victims of ID fraud. This can cause severe economic harms; the average family loses in excess of $1,000 when a child falls victim to identity fraud. In 2021 alone, fraud losses linked to child identity fraud totaled $918 million, averaging $737 per family.16 Likewise, data theft or misuse can create security concerns. We have seen how, for example, data collected about adults by tech companies has been misused by staff to track ex partners and celebrities,17 and it is unclear if young people’s data is any better protected.

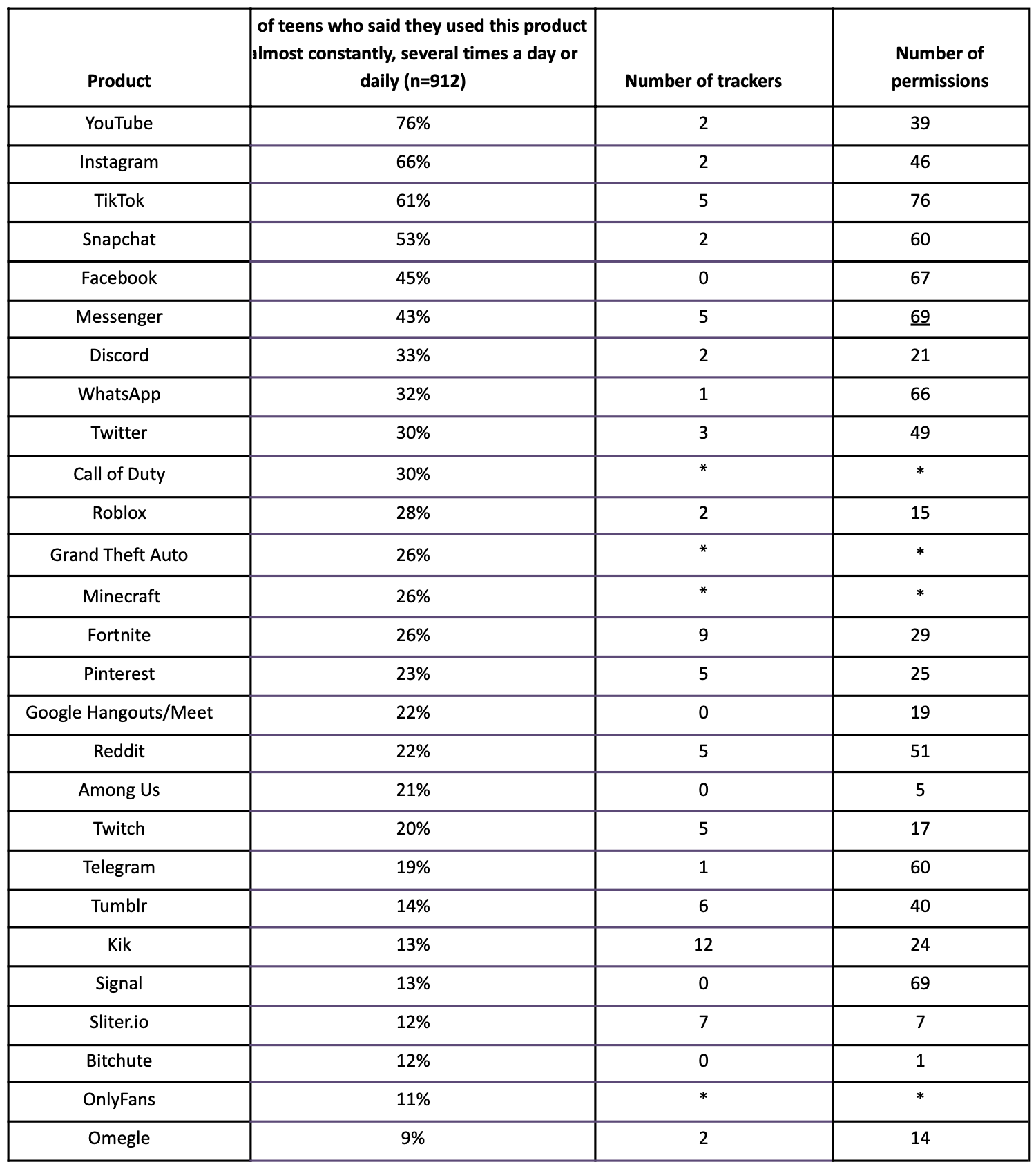

Our poll asked young people to identify apps they used almost constantly, several times a day, daily and less frequently. We explored the number of trackers embedded in these products, and the amount of permissions they requested (such as access to the camera, or phone book) on an android phone, for the apps that were in frequent use by many teens. As figure 4 highlights, the average American teen would be followed by a significant number of trackers in their average digital day. If a young person uses YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, Snapchat, Facebook, Messenger and Discord all in a day—all of which at least one third of young people say they use daily— they might be followed by 18 trackers each day.

Manipulative advertising and sales features

Many apps and platforms use ‘behavioral’ or ‘targeted’ advertising that uses all of the data they have harvested about young people to push them advertising. These ads are unavoidable. All of the top 5 apps popular with American teens for example,19 serve young people advertising targeted to their demographics for example, and 60% of them target young people based on their online behavior too. Younger children are no more protected either, 95 percent of children’s specific apps included at least one form of advertising.20

The impact of behavioral advertising on young people is poorly understood, but evidence suggests that they are affected by it. For example, research has shown that despite young people’s privacy concerns, they do not appear to be able to effectively safeguard themselves from the persuasiveness of this advertising.21 Other research shows that when teenagers are provided with more information and ‘debriefed’ about how behavioral advertising works, any initially strong intentions to make purchases are moderated.22 Research on younger children have also found that “children seem to process targeted online advertising in a noncritical manner”23 vis a vis adults.

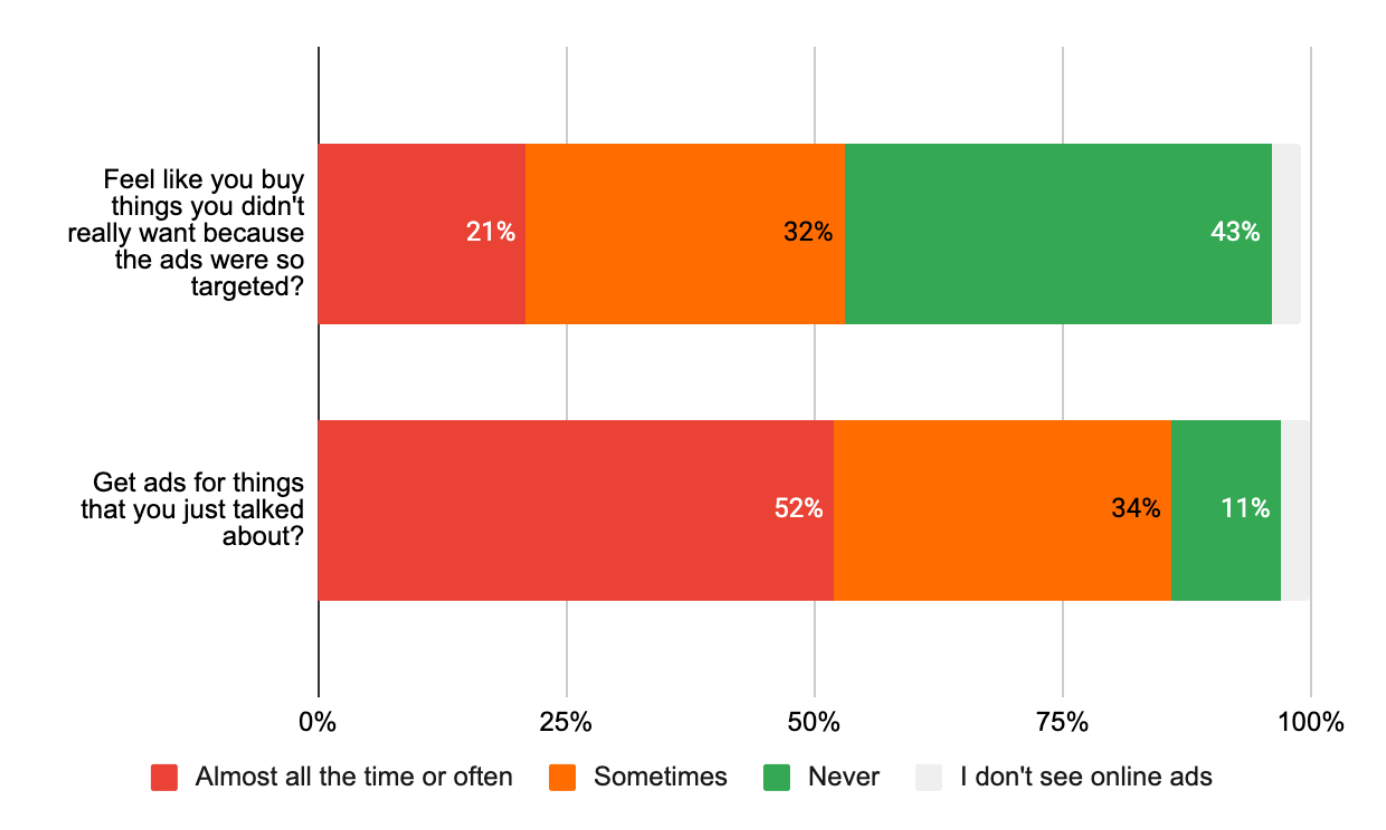

This unfair persuasive power appears to have materially affected American teenagers. In March 2023, working with YouGov we asked 912 American teenagers if they felt they had purchased things they didn’t really want to because the ads were so targeted. The majority of young people agreed; 21% said this happened almost all of the time or often, and a further 32% said it sometimes happened.

We also asked about the perception of how targeted these ads were. Over half of the young people we asked said they almost always or often got ads for things they just talked about, and a further 24% said this often happened.

We also asked young people in the poll if, and how often, they wanted to see targeted ads online. Almost a third (31%) said they did not want to receive targeted ads, and 40% said they only wanted to see them sometimes. This is in stark contrast to the frequency that they are currently receiving ‘stalker ads’. It’s worth noting that targeting young people does not meet community expectations. A 2021 poll found that 88 percent of parents support banning the use of kids’ data to serve them targeted ads.24

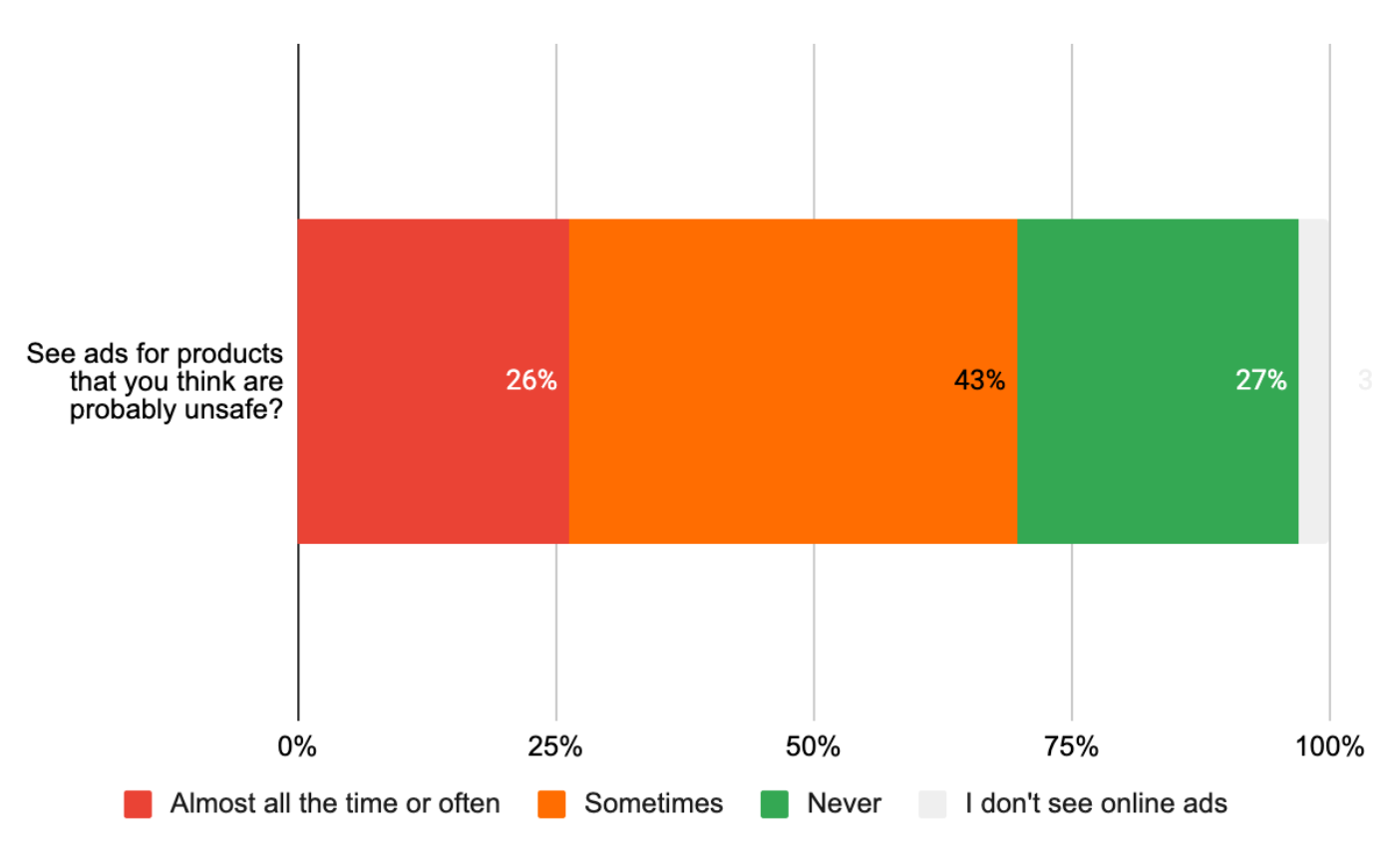

Not all ads online are credible. We asked young people how often they felt that they were served ads for products they felt were probably unsafe. A quarter of young people said they received ads that were probably unsafe online almost all of the time or often, and 43% said they sometimes received them. Tellingly, only 27% said they did not receive ads online for products they felt were unsafe.

Not all American young people were served unsafe ads equally, and our research found that Black teenagers reported seeing more unsafe ads than other young people, as did young people who identify as LGBTIQ+.25

We also asked young people about the frequency of purchases from ‘loot boxes’. Loot Boxes are a design feature that allows young people to buy ‘random rewards’ in an app or game. For example, teenage gamers can purchase a ‘mystery box’ in a football game that could include their favorite players. Loot boxes often come with advertised odds, which makes them strikingly similar to gambling.26 In our poll, 18% of young people said they purchased loot boxes almost all the time or often, with an additional 28% sometimes making purchases. That’s 45% of American teens who have engaged in a very gambling-like activity online.

How design codes might help

These design harms do not happen by accident, nor are they inevitable in the digital world. Online platforms and products can simply redesign themselves to minimize the risk of these harms. But this does not currently happen.

A number of US states are considering introducing Age Appropriate Design Codes that would require companies to undertake a risk assessment of their products, and explore how their designs affect these harms. They would be required to both identify and minimize risks, to reduce the harms that occur as a result of young people using their platforms. Each of the design harms identified in this report should be identified and mitigated as a result of this process. It would also require other common sense moves, like for young people’s accounts to be set to the most private settings by default when young people join, and to not collect geolocation data where it isn’t necessary.

1 De Montfort University 2022 DMU research suggests 10-year-olds lose sleep to check social media https://www.dmu.ac.uk/research/research-news/2022/dmu-research-suggests-10-year-olds-lose-sleep-to -check-social-media.aspx#:~:text=Research%20support-,DMU%20research%20suggests%2010%2Dyea r%2Dolds%20lose%20sleep%20to%20check,up%20to%20use%20social%20media

2 Allison Zakon 2022 ‘Optimized for addiction: Extending product liability concepts to defectively designed social media algorithms and overcoming the communications decency act’ Wisconsin Law Review (5) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3682048

3 Kevin Roose 2019 ‘The Making of a YouTube Radical’ New York Times

4 Louise Matsakis 2019 ‘On TikTok, There Is No Time’ Wired

5 For example, Instagram allows users to set daily time limits to prevent overuse. Consumer’s used to be able to self define their daily limit, including setting limits at 10 or 15 min. Earlier this year, Meta set a new ‘limit’ to these daily limits. Consumers can only now set a daily limit of 30 minutes or more (See Natash Lomas 2022 ‘Instagram quietly limits ‘daily time limit’ option’ TechCrunch)

6 Pew Research Center 2022 Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022

7 As defined in DSM5 onwards (See American Psychiatric Association 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing Arlington). See also Cecilie Andreassen 2015 ‘Online social network site addiction: A comprehensive review’ Current Addiction Reports doi:10.1007/s40429-015-0056-9, who explores the potential for social networking sites to be addictive

8 Douglas Gentile 2009 ‘Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: a national study’ Psychological Science 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02340.x.

9 Sarah Domoff, Aubrey Borgen, Sunny Jung Kim, Jennifer Emond 2021 ‘Prevalence and predictors of children’s persistent screen time requests: A national sample of parents’ Human Behavior and Emerging Tech doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.322

10 Abigail Hess 2019 ‘Research continually shows how distracting cell phones are—so some schools want to ban them’ CNBC

11 See De Montfort University 2022 as above

12 Forthcoming research How design codes could help reduce racial disparities between youth online

13 Pew Research Centre 2022 Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022 https: //www.pewresearch.org/internet /2022/08/10/teens-social-media-and-technology-2022/

14 As made public in Alexis Spence et al. v. Meta, U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, Case No. 3:22-cv-03294 (filed June 6, 2022) (“Spence Complaint”) p. 11-12, Growth, Friending + PYMK, and Downstream Integrity Problems.

15 Forthcoming research How design codes could support young LGBTIQ+ people online

16 Tracey Kitten 2021, Child Identity Fraud

https: //javelinstrategy.com/research/child-identity-fraud-web-deception-and-loss.

17 Jo Ling Kent, Chiara Sottile & Michael Cappetta 2016 ‘Uber Whistleblower Says Employees Used Company Systems to Stalk Exes and Celebs’ NBC News

https: //www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/uber-whistleblower-says-employees-used-company-systems- stalk-exes-celebs-n696371

18 According to Exodus Privacy https://reports.exodus-privacy.eu.org/en/

19 Taken from figure 4 above.

20 Marisa Meyer, Victoria Adkins, Nalingna Yuan, Heidi Weeks, Yung-Ju Chang & Jenny Radesky 2019 “Advertising in Young Children’s Apps: A Content Analysis.” Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics:

https: //pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30371646/#:~:text=DOI%3A-,10.1097/DBP.0000000000000622,-Full% 20text%20links.

21 Specifically, higher levels of targeting using more personalized data generates stronger responses among teens regardless of their concerns about privacy. Michel Walrave, Karolien Poels, Marjolijn L. Antheunis, Evert Van den Broeck & Guda van Noort 2018 “Like or dislike? Adolescents’ responses to personalized social network site advertising,” Journal of Marketing Communications,

https: //doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2016.1182938.

22 Brahim Zarouali , Koen Ponnet, Michel Walrave, Karolien Poels 2017 “”Do you like cookies?” Adolescents’ skeptical processing of retargeted Facebook-ads and the moderating role of privacy concern and a textual debriefing” Computers in Human Behavior http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.050.

23 Eva van Reijmersdal, Esther Rozendaal, Nadia Smink, Guda van Noort & Moniek Buijzen 2017 “Processes and effects of targeted online advertising among children” International Journal of Advertising

https: //doi-org.ezproxy-b.deakin.edu.au/10.1080/02650487.2016.1196904.

24 Accountable Tech 2021 Accountable Tech Frequency Questionnaire 2021

https: //accountabletech.org/wp-content /uploads/Accountable-Tech-Parents-Poll.pdf.

25 Forthcoming research How design codes could help reduce racial disparities between youth online and How design codes could support young LGBTIQ+ people online

26 James Close & Joanne Lloyd 2020 Lifting the Lid on Loot-Boxes

https: //www.begambleaware.org/sites/default /files/2021-03/Gaming_and_Gambling_Report_Final.pdf.